Pioneering women in Spartanburg healthcare

Editor’s note: This weekly series celebrating the 100th anniversary of Spartanburg Regional Healthcare System is excerpted from “Commitment To Our Community: 100 Years of Spartanburg Regional Healthcare System.”

Dr. Hilla Sheriff aspired to become a medical missionary in South America until she discovered the women and children of Spartanburg County and the greater Piedmont area needed her more. Between 1928 and 1932, South Carolina had the highest maternal and infant mortality rates in the United States. The state also had high levels of poverty.

Sheriff, a graduate of the College of Charleston and the Medical College of South Carolina, came to Spartanburg as an intern at Spartanburg General Hospital. She established a pediatrics practice in Spartanburg in 1929 to address health disparities and because she found support from Dr. Rosa Hirschman Gantt and Dr. Hallie Rigby, also pioneering women in medicine.

Gantt graduated in 1901 from the Medical College of South Carolina and became the first woman to practice medicine in Spartanburg County. She was an eye, ear, nose and throat specialist in Spartanburg for 30 years, an officer for the South Carolina Medical Society and president of the American Medical Women’s Association Board. Gantt developed a program of medical examinations in local schools, conducted workshops on domestic hygiene and tuberculosis prevention techniques and led a campaign that established public playgrounds.

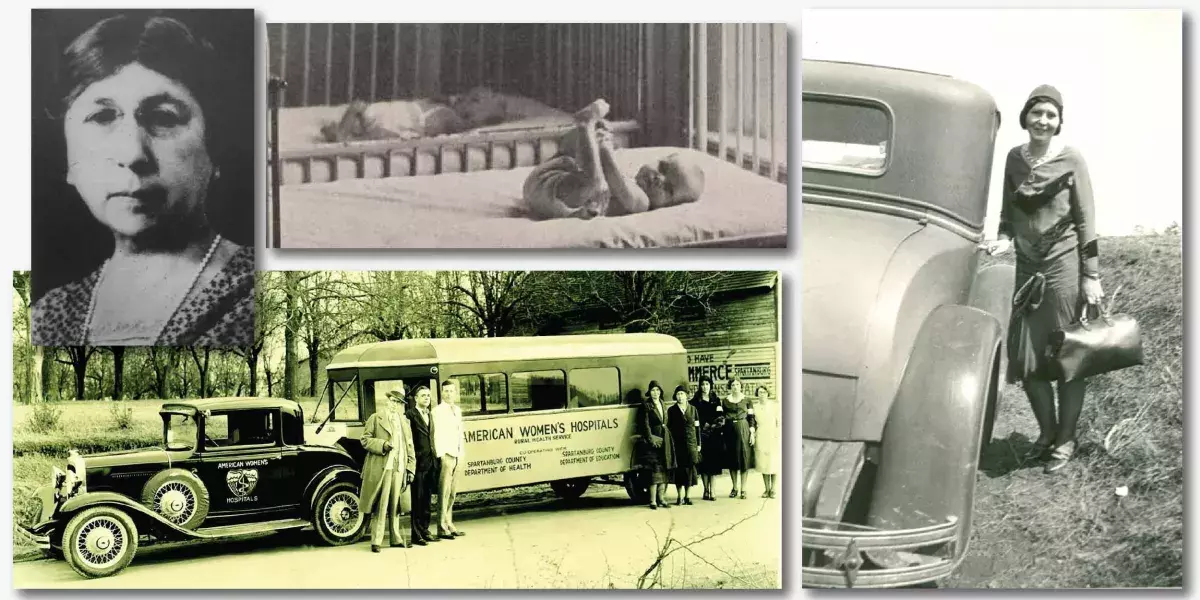

Gantt also started a project called “Bringing Health to the Country.” Nurses, physicians and dentists traveled with a fully equipped mobile medical and dental trailer throughout the county’s rural communities. They offered immunizations, general exams, prenatal care, family planning and education regarding pellagra, a disease caused by niacin deficiency that reached epidemic proportions across the South at the turn of the 20th century.

Rigby, a 1917 Johns Hopkins graduate, shared a practice in Spartanburg with her husband. She met the medical needs of their practice while her husband performed surgeries. The doctors worked primarily with women and children who lived and worked in the area’s textile villages and mills. All three were affiliated with the Spartanburg County Health Department and Spartanburg General Hospital in the late 1920s. In 1931, at the request of Dr. Gantt, the American Women’s Hospitals asked Dr. Sheriff to establish American Women’s Hospitals programs in Spartanburg and Greenville. The American Women’s Hospitals, an organization founded by women physicians in 1918 to provide medical care to the people of war-torn France, eventually established hospitals around the world. The Upstate South Carolina units were the organization’s first programs in the United States.

Sheriff operated the American Women’s Hospitals “healthmobile” in Spartanburg’s and Greenville’s rural and textile mill communities. Under Sheriff’s training and guidance, pellagra was reduced by half in Spartanburg between 1931 and 1933. Her healthmobile also provided prenatal and postnatal care.

Sheriff institutionalized American Women’s Hospitals programs after 1933 when she was named the assistant director of the Spartanburg County Health Department. Four years later, she assumed the directorship. As the state’s first female health officer, Sheriff remained focused on the healthcare needs of women and children. She increased the number of prenatal clinics and immunization programs and started the first family planning clinic associated with a health department in the United States. She also secured funding for contraceptive research.

In 1936, Sheriff received a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship to study public health at Harvard. She became the second woman, the first American woman, to earn a master’s degree in public health from the university.

Sheriff’s work in Spartanburg and with Spartanburg General provided the foundation for a long career, during which the health of South Carolina women and children was substantially improved. In 1940, she moved to Columbia to become the assistant director for maternal and child health for the State Board of Health. She spent much of the 1940s and 1950s developing programs to license and train midwives, arguing that to bar midwives from practicing in the Jim Crow South would deny many African-American women any form of medical assistance during childbirth.

Later in her career, Sheriff focused on the prevention of child abuse, leading the efforts to pass a state law that requires physicians to report cases of suspected abuse. She retired in 1974 as the deputy commissioner of the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control and chief of the Bureau of Community Health.